What’s in a Frame?

Any scholarly analysis of adaptation needs to address filmic as well as literary evidence. The summary overview below outlines the formal features you could cite in the library sequence of David Fincher’s Se7en (1995). (Admittedly, this film is not an adaptation. That said, this sequence below renders reading and literary interpretation, so it is a useful case study for our purposes.)

First, the clip in its entirety:

The sequence utilizes cross-cutting (a.k.a. parallel editing) to unite two separate scenes in different locations. The first cut to the apartment may be a bit mystifying to viewers who are unfamiliar with the film, and the story being told therein, but the repeated movements back and forth between the shots in the library and the shots in the apartment create a parallelism that encourages us to assume that the separate actions in different locations are (a) occurring at the same time and (b) related in some fashion.

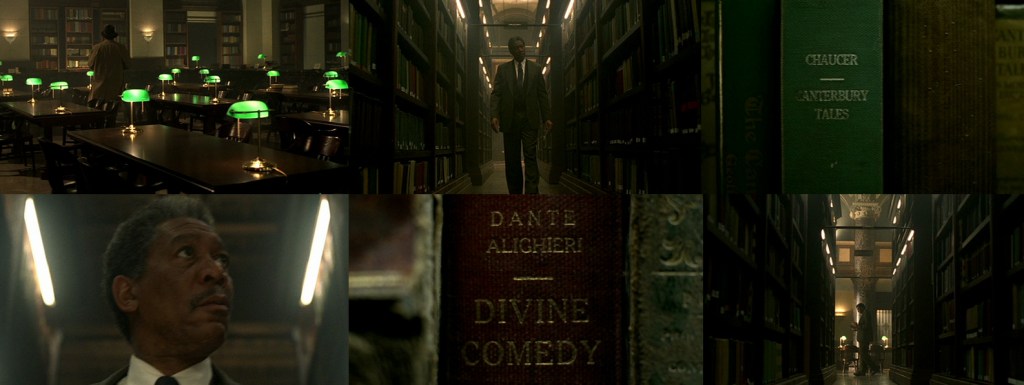

Even if we don’t know that Morgan Freeman plays a world-weary detective named Somerset, and that Brad Pitt plays his idealistic partner, Mills, we understand where the characters are, and how they relate to one another, because the clip relies on continuity editing. We may not get an establishing shot that shows us the exterior of the library, but we know, from dialogue and décor, where Somerset is, and the mobile camera, which tracks Somerset as he enters the building, effectively moves us through the location, first by following Morgan Freeman’s character, then by following the guard who walks up the steps. Angles alternate between high and low (notice how our initial shot of Somerset shows him from an aerial or bird’s eye view, whereas subsequent shots are positioned at a low or slightly below eye-level angle), but we always understand where he is in the library, and how this position relates to that of the guards up above, because the camera does not violate the 180-degree rule.

A series of match cuts also aid in continuity. Numerous eye-line matches establish that various shots that may appear unrelated (crime scene photos, book spines, Gustav Doré’s illustrations for the Inferno) are actually images that our central characters are viewing. These matches also aid in spatial continuity, as we implicitly understand where the viewed image or subject is in relation to the subject that is viewing. This is as true of Mills looking at crime scene photos as it is of Somerset looking up at the guards in the library (and, it should be said, of the main guard looking down on Somerset).

In the case of Somerset, eye-line matches frequently allow the filmmaker to shift the axis of action without disorienting the viewer. These recurrent shots also exemplify point of view editing, a hallmark of cinematic continuity. Fincher, who is known for his clever use of pov, adds some interesting stylistic flourishes to these matches. At one point, we see Somerset put on glasses, then we see a book spine that comes into focus. Here Fincher (or more correctly his cinematographer, Darius Khondji) manipulates focal length to replicate the effect of reading glasses.

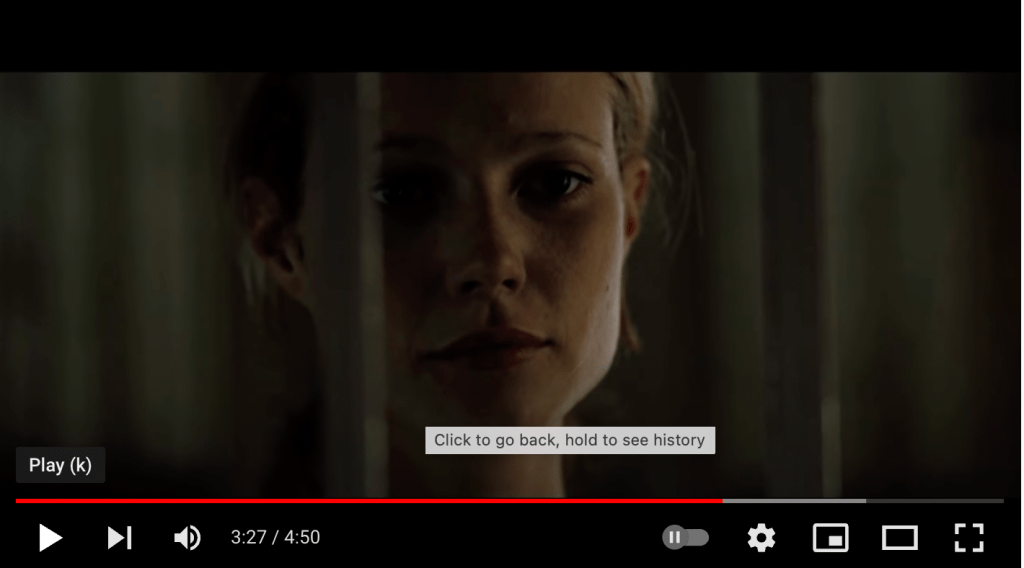

The filmmakers also invert the normal shot pattern in some of their eye-line matches. Viewers see what Mills’ wife sees—Mills, from behind, sitting on the couch, with crime scene photos splayed about him, and the TV on—before they see Mills’ wife (played by Gwyneth Paltrow) looking compassionately at her husband. Here we see what is “matched” before we even get the “eyeline.”

These eye-line matches are complemented by numerous graphic matches, which cut on similar imagery or actions. A shot of a gruesome crime scene photo of a dead man’s feet (a photo that Mills is pondering in his apartment) is followed by a shot of Somerset’s feet as he walks the stacks of the library. Shortly before that, a shot of Mills, looking pensively off screen left is followed by Somerset gazing in the same screen direction. These graphic similarities augment the relationship established through the use of parallel editing.

Although this sequence isn’t as blatantly obvious as a fashion (or make-over) montage in a rom-com, or a training montage in a sports film, it too serves as an elliptical editing device that cinematically conveys a long stretch of time through the juxtaposition of representational shots. Whether fast-paced, in order to capture the dynamism of action, or more slowly paced, in order to represent a greater duration, monotony, or repetition, Hollywood montage compresses time in order to “speed up” the plot. Somerset’s and Mills’ “all-nighter” is only on the screen for a few minutes. We experience the extent of the actual duration through transitional devices and sound choices. In addition to the numerous match cuts, the clip employs frequent dissolves within the separate scenes. These effectively demonstrate how little has changed over time, as the blending of images connote that modest movement “forward” is merely incremental.

The music that serves as a sound bridge, Bach’s “Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Air,” aids in this experience by setting a relatively slow tempo. While this music, like most music deployed in montage, works to combine the disparate shots into a harmonious whole, it is not, as is usually the case, just off screen and non-diegetic. We first hear the classical music when one of the police guards, in response to Somerset’s quip, turns on the stereo. Because we initially see the source of the sound, and the characters on screen hear it as well, the music begins as on screen, external, and diegetic. This changes when we cut to Mills’ apartment. There is no break or disruption in the sound, but the detective, who is not in the library, and does not have a stereo on, could not possibly hear the classical strains that play when audiences witness his scenes. (The only thing we can be sure Mills hears is the TV he turns on when he can no longer focus on the investigation. This ambient sound is interlaid with the music that acts as bridge.) In these instances, the Bach suite becomes off screen and non-diegetic, which is typical of montage sound bridges.

As is the case in many films, different scenes have similar mise en scenes. The sequence includes two different locations, yet each location is lit and shot in a similar fashion. Both the library and apartment have low-key lighting (which significantly renders even “light” colored objects somewhat murky), and, once the research begins in earnest, each detective is framed in a similar way. Both Somerset and Mills are briefly shown in aerial shots that connote their relative powerlessness in the face of the enormity of their task, and both are frequently shown in close-ups. The dominant angle (as is typical of Fincher) is slightly below eye-level (a cinematic choice that may symbolically register the fact that Fincher’s films focus on the darkness that lurks beneath apparent normalcy). The color palates of each location are also similar, which unite the settings, despite differences in décor.

Admittedly, the library sequence is not a particularly noteworthy portion of the film, as it is serves no major symbolic, thematic, or stylistic function, but it does contain a great deal of filmic detail, as most film clips do. Your analyses should consider such detail and select the elements that are most significant (and conducive to your argument).