Since its publication in 1922, T.S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land, has been the fodder for much critical discussion. Numerous reviews, articles, and book-length studies have attempted to register its innovation and aesthetic value as well as “decode” the text itself.

Obviously, a hand-out such as this cannot possibly reflect all critical approaches–or exhaust the full interpretive meaning of a fragmentary work that scholars continue to debate–but it can offer some important context and critical insight into fairly standard readings of the poem.

You can either being scrolling through this admittedly long guide or click on a topic to jump to that section. Take your pick.

The Pound Era

Hugh Kenner’s categorization of the modern period as ‘The Pound Era’ may ultimately relegate women writers to “minor” elements in a masculine movement, but it does rightly note how influential Ezra Pound’s criticism proved to be. The iconoclastic writer shaped many modern moods and trends.

Although a celebrated poet in his own right, Pound found his greatest fame as a collaborator/editor with some of the most gifted artists of the time. He exerted great influence on the most important poet of the early modern period, Yeats, and helped to champion the poet who would become the most celebrated artist of the later portion of modernism (what is often called High Modernism), T.S. Eliot.

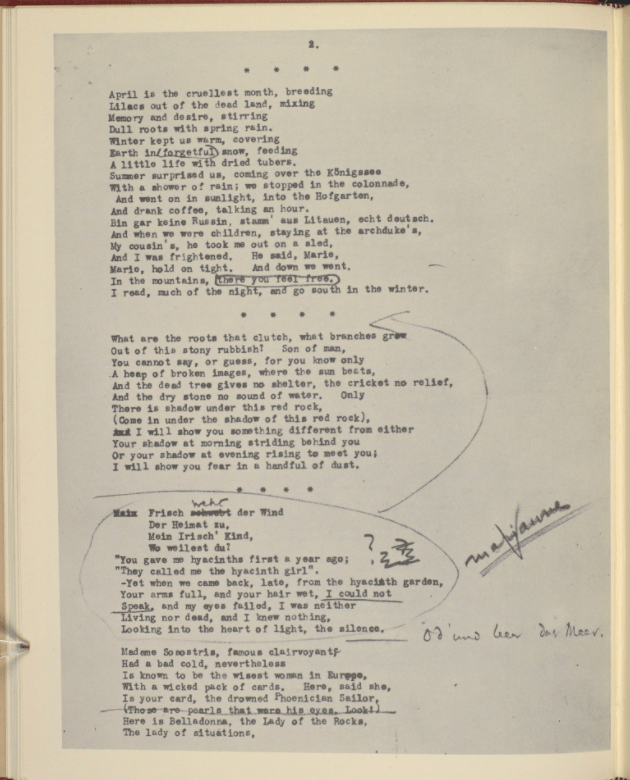

Pound may have infamously contended that Eliot had “modernized” himself (unlike a poet such as Yeats who had to be alternately lulled and jolted out of his strong Romantic sensibilities), but that does not mean that Pound served no role in “modernizing” Eliot’s work. Early drafts of The Waste Land show a poem nearly double in length and weaker (according to most estimations) in symbolic import.

Urging Eliot to “make it new,” Pound helped eradicate portions where the poet included overt explication and he often slashed away at cumbersome narrative voices. Eliot acknowledged his debt to Pound not only by dedicating the work to his critical collaborator, but also by contending that Pound was “il miglior fabbro,” or “the better artisan.” (For more, see Mark Ford’s “Ezra Pound and the drafts of The Waste Land.”)

A Waste Land is a Waste Land is a Waste Land?

Among the many changes to The Waste Land during the process of revision was a change in title. Early in the drafting process, Eliot had envisioned naming his work, “He Do the Police in Different Voices,” a title ‘borrowed’ from Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend (the full quote has the Widow Higden saying to her adopted son, “Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the police in different voices” ).

The epigraph was also different. Instead of quoting from The Satyricon, Eliot had begun his work by inscribing the last lines of a mad and dying Kurtz, “The horror, the horror.” Although Eliot eventually dropped the reference to Heart of Darkness, and included a different “voice,” the initial inclusion of Conrad’s words can tell us a great deal about the poem. Spiritually bereft and destroyed by society, Kurtz himself is a modern “Hollow Man.” He has much in common with the “lost souls” who march across the London Bridge to work in “The Burial of the Dead.”

The Mythical Method

Pound, of course, wasn’t the only writer/critic of the age. Eliot himself was a very famous critic, and he often turned his scrutinizing gaze to the works of others. In a review of James Joyce’s Ulysses (a novel considered by many to be the finest work of the modern period, if not of the 20th century), Eliot coined the phrase, “mythical method.” This new term was meant to refer to artistic attempts to “renew” or “invigorate” mythical structures or stories by placing them within modern contexts. In his schema, works such as Joyce’s Ulysses (or, we could add, Shaw’s Pygmalion or Yeats’ “No Second Troy”) regenerated the usefulness of the myths while making them “new” and suitable for the age.

A critic could contend that Eliot himself utilized the mythical method while composing The Waste Land. The poem refers to a vast number of myths and legends, but it most clearly sustains a connection with the quest for the Holy Grail. Like many 19th-century artists (such as the Pre-Raphaelites), Eliot found himself drawn to a medieval story line, but his treatment of the legend (unlike, say, Tennyson’s Idylls of the King) sought to give the quest relevance in the modern world.

The Grail Legend

The Quest for the Holy Grail is just what its name implies, a quest undergone by knights to recover the Holy Grail, or the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper. According to most sources (including Malory), the Knights of King Arthur’s Round Table were at Camelot when they saw a brief vision of the Grail. This vision prompted them to leave the joys of Camelot and to recover the sacred vessel.

Although different versions have different knights attempting, failing, and succeeding at securing the Grail (and include various supporting characters, such as Grail Knights who supposedly guard the vessel), the general contours of the tale remain the same. The Questing Knight, on his journey, encounters a Chapel which is (unbeknownst to him) the Chapel Perilous. The Knight enters, encounters the Grail Maidens, and sees various visions and wonders. He also encounters a dead or dying king (The Fisher King) who is the ailing sovereign of the land. Specifics of the Fisher King’s wound (the Dolorous Blow dealt him) vary–many see it as sexual in nature–but all agree that the wounding of the king is the cause of the barrenness of his land (the “Waste Land” about the Chapel Perilous). The Knight, if he is indeed the Quester meant to break the spell, asks the requisite questions and is thus able to secure the actual Grail (not merely a vision of it) with which he heals the Fisher King and restores fertility to the land.

While versions of the Grail legends, and interpretations of it, had been circulating throughout the western world from the medieval period on, Eliot himself relied upon a very specific study which was published in 1920 by a scholar named Jessie L. Weston. In From Ritual to Romance, Weston set about to show how the ancient and pagan rituals of Celtic peoples (which she sees as prototypes for the Grail legend) became transmogrified into a medieval Romance replete with Christian connotations.

Eliot himself goes out of his way to note his indebtedness to this study, and he even contends that a perusal of the text will do more to help a reader understand his poem than his own stylized notes will: “Miss Weston’s book will elucidate the difficulties of the poem much better than my notes can do; and I recommend it (apart from the great interest of the book itself) to any who think such elucidation of the poem worth the trouble.”

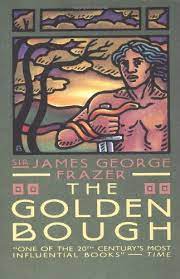

The Golden Bough

The other work of scholarship Eliot cites in the preface to his notes is Sir James Frazier’s The Golden Bough: “To another work of anthropology I am indebted in general, one which has influenced our generation profoundly; I mean The Golden Bough; I have used especially the two volumes Adonis, Attis, Osiris. Anyone who is acquainted with these works will immediately recognize in the poem certain references to vegetation ceremonies.”

The anthropological study, which was begun as an attempt to “explain the remarkable rule which regulated the succession of priesthood of Diana at Aricia” (Frazer v), morphed into an analytical articulation of the mythic patterns that undergird all cultures. (The successful study appeared to provide what George Eliot’s fictive pedagogue, Edward Casaubon, devoted his life to finding: the “key to all mythologies.”)

Of most interest to Frazer were fertility rituals: rituals that involved the empowerment and eventual sacrifice of sacred kings. Although Frazer takes great pains to distance the “primitive” and “pagan” rites of ancient and/or “uncivilized” cultures from the obvious parallels with Christianity (which also has a sacred figure who dies, is eaten, and brings rebirth through resurrection), he nonetheless notes the ways in which all cultures seem to enact this seemingly primordial urge.

In his work, he places extended studies of figures such as Adonis, Attis, Osiris, and Balder alongside the mythical “underworld” journeys of heroic kings such as Odysseus and Aeneas. In each case, and in each cultural context, Frazer finds that this death and rebirth serve as a pattern to ensure a smooth kingly succession and as a way to regenerate the fertility of the land itself. Noting what the psychoanalyst Carl Jung would call “archetypes,” Frazer does seem to suggest that there is some validity to the notion of a “collective unconscious.”

Okay, so how does all of this relate to Eliot? Well, Eliot’s very choice of the myth of the Fisher King already places his “mythical method” in line with Frazer’s theories of sacred kingships, for the Fisher King can be seen as a later embodiment of this ancient figure. Eliot, who had read and admired Frazer, also alludes to numerous attempts at (often parodic) fertility rituals throughout The Waste Land (the buried corpse being dug up by a dog, the Tarot card of the “Hanged Man,” and the fear of “Death by Drowning”). Eliot’s ironic purpose, for the most part, is to show us how these rituals cannot be performed properly, and hence cannot be truly effective, in such a degraded age.

Entering the Underworld

If you felt like you were shuttling through the circles of Dante’s hell while you read The Waste Land, you’re not alone! As Eliots’ footnotes make clear, references to Dante’s descent into the Inferno (and his sojourn in Purgatory) abound. Many scholars, seeing these constant allusions as incredibly important, contend that The Waste Land itself needs to be read as a journey to the underworld. Eliot’s hell may not have an identifiable Satan nor a sole guide (although Tiresias does serve an important function), but it does give us a glimpse of the “Hollow Men” and “lost souls” who inhabit the degraded and often nightmarish landscape.

This reading strategy (i.e., considering the movement through The Waste Land as poetic journey into hell) is further supported by the epigraph from Petronious’ Satyricon. It references a mythical woman (the Cumaean Sibyl) whose immortal yet aging body causes her to yearn for death.

This famed figure features prominently in Roman myth and history. It is she who informs Aeneas that he must pluck to Golden Bough to safely navigate his way through the land of the dead. Eliot, who was aware of this myth (through Frazer and other sources, including Virgil), thus consciously alludes to a descent to the underworld at the beginning of his poem. The fact that he chooses to focus on the benighted and infertile aspects of the sacred Sibyl, though, may suggest that the reader’s descent will be less fruitful than Aeneas’.

So what would Edward Said think the Thunder said?

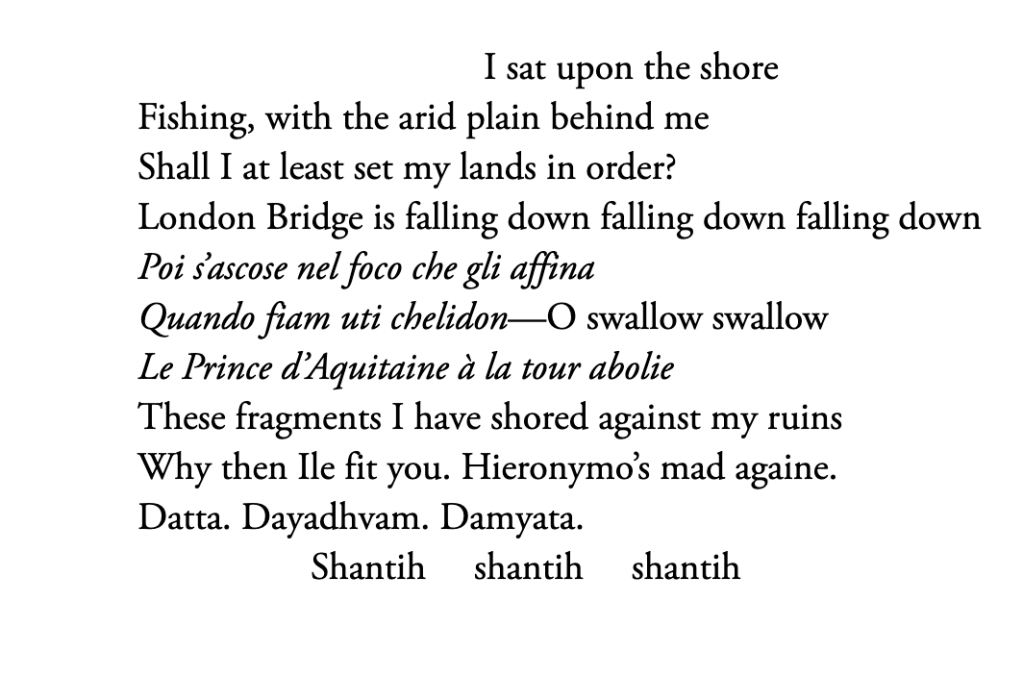

Well, The Waste Land is obviously not Eliot’s “Ode to Joy,” but it isn’t necessarily his “Ode to Dejection” either. Critics may squabble over the meaning of the death of Phlebas the Phoenician in “Death by Water” (is it a peaceful end, a further instance of the “waste land’s” sterility, or a foreshadowing of the ritualistic death of the vegetation god?), but it is fairly clear that Eliot laid out a glimmering of hope in the last passages of the poem. Having finally come to the metaphorical “Chapel Perilous,” where we can see the Fisher King sitting upon the shore, we encounter not a questing knight asking three ritual questions, but references to the Upanishads. In particular, we are alerted to the three “Great Disciplines” that the Hindu Creator God delivers in a sermon: Datta (Give), Dayadhvam (Sympathize), Damyata (Control). So, basically, a poem that relies upon a Christianized medieval romance (which began, as Weston tells us, as a pagan fertility ritual) ends with a reference to the “spiritual” wisdom of an “Asian” religion.

Although it would be erroneous to contend that Eliot lays out a system of belief, or a new cosmology, in this work (religious queries are better answered in The Four Quartets), it cannot be denied that Eliot’s movement from the degraded and debased rituals of the west to the potentially redemptive powers of “eastern mysticism” allies him with modernist sensibilities. Keep in mind that the modern world was literally rocked by Nietzsche’s contention that there was no God–a contention that seemed only to be affirmed by the horrors of the First World War. In response to this theological crisis, many new religious movements, such as Theosophy, sprang up, attempting to suffuse the seemingly “dead” forms of occidental Christianity with strong “spiritual” elements, elements usually borrowed from “eastern” religions.

The arts also borrowed liberally from “eastern” ideals and beliefs. Japanese painting and design had a profound impact on artists as diverse as Whistler and Beardsley. In literary circles, Pound, Eliot and Yeats all found inspiration in eastern forms (Pound in haiku and Chinese pictographs–which served as his “ideograms;” Eliot in Hindu mysticism; and Yeats in the stylized Nōh theatre). Although this interest in other cultures and beliefs was reflective of the strong cosmopolitan strain of the modernist movement, it can also be seen as reflective of an “orientalist” ideology. In such schemas, “eastern” works are not accepted in their own right or on their own terms, but as necessary correctives or panaceas for an ailing west. In this uneven cultural exchange, the “east” again gets figured as a place of radical alterity and as a projective site for occidental fears and desires.

Symbolist Poetry

Like most Anglo-American artists of the modern period, Eliot had read Arthur Symon’s study of the French Symbolist poets. Eliot, though, also read the work of the poets themselves. He was obviously familiar with the verse of Rimbaud, Mallarme, Laforgue, and Valery, but he chooses to pepper “The Waste Land” with quotes from Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal, a work that embodied a tragic sense of life and relied upon the juxtaposition of antipodes such as attraction and repulsion, the sublime and the mean, and heaven and hell to work its shocking effect.

- Symbolism set about to eradicate narrative, exposition, and didacticism

- It strove to create a poem around a single image or sensation

- It attempted to use the subconscious associations of the mind (thus creating a form of literary “synaesthesia”)

It may seem as if some of the “revolutions” the Symbolists put forward are not very revolutionary at all. In particular, we could cite many “traditional” and “standard” poems that revolve around a single image or sensation. What makes the Symbolist poem different from, say, Wordsworth’s joy in nature is the writer’s conscious attempt to create every image or emotion completely anew. They too rejected the “artificial” poetic diction that Wordsworth jettisoned, but they also saw in Wordsworth’s overt explication and clear and precise symbols an overworked and unimaginative “formula” that told the reader what to think or feel instead of allowing him/her to experience the emotion or image in a new way. For this reason, Symbolists (and Imagists) avoided using “standard” symbols to embody moods or ideas. (Falling leaves would not be clear-cut patterns for Autumn and approaching death; sunrise would not be an unproblematic signifier for regeneration or rebirth.) Symbolists obviously used symbols, but they attempted to resignify them in a new way so that the reader would experience, say, sunlight in a different fashion (and within a particular context).

OH NO–It’s the Objective Correlative!

As noted above, Eliot was, like many others, influenced by the Symbolists. If we are to read The Waste Land as a symbolist poem, though, we have to consider the scholarly notes and arcane references to mythic rituals as cultural fragments that craft a modern ruin. The various allusions are not important in and of themselves (because symbolic literature refuses to represent a one-to-one correlation between “reality” and the work of art); rather, they are constituent elements that assemble into an objective correlative for modern angst.

This of course, still leaves the question: what is an “objective correlative”? According to Eliot (who defined the term “Hamlet and His Problems“), the objective correlative is the impersonal presentation of emotion in a work of art. It is “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion, such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately invoked” (para. 7). Such a correlative is necessary, in Eliot’s estimation, because readers require an “objective” method for accessing an emotion they are expected to sense.

To put this argument more directly in terms of The Waste Land (and symbolist poetry), if a poet can no longer rely on almost clichéd images to bring about an emotion or feeling, how is s/he supposed to affect the reader? The answer, for Eliot, is to put in place a sequence which, when played in the proper order, produces the desired effect. Critics have argued that the numerous and almost baffling references to myths, arcane religions, various literary works, and historical epochs in Eliot’s masterwork do just that. These references are not provided as hidden treasures in an archaeological site that the reader is expected to unearth, study, and piece together to produce a set esoteric meaning; rather they are presented as “objects,” “a situation,” and “chains of events” designed to produce a “sensory experience” of the modern condition.

Collage

In the plastic arts, the technique of collage is effected by the combination of unlike or seemingly unrelated elements placed together to create a “whole”–for example, the inclusion of newspaper clippings or cigar labels in a painting, or the combination of photos, words, and drawings pasted on a raised surface. As the Poetry Foundation relays, “Collage in language-based work can now mean any composition that includes words, phrases, or sections of outside source material in juxtaposition.”

Although Eliot uses the technique of collage throughout The Waste Land, it is perhaps best seen in the last section, “What the Thunder Said.” According to Jacob Korg, the “quotations and the parodic insertions imitative of quotations. . .are intrusion from the external world, ‘found objects,’ which assert their reality within the space of the poem. They create an effect of discontinuity even when they are relevant to their contexts, because, like the papers pasted to a cubist canvas, they affirm beyond all else their own presence; the reader is free to connect them with the themes of the poem by using the associations they bring with them” (125).

(Source: Korg, Jacob. “The Waste Land and Contemporary Art.” Approaches to Teaching Eliot’s Poetry and Plays. Ed. Jewel Spears Brooker, MLA, 1988, pp. 121-27.)

Palimpsest

A palimpsest is literally a writing surface which bears the imprint of former writings. (Ever seen a hokey crime drama where a P.I. scumbles across a hotel notepad to uncover the address still imprinted below? That notepad is a palimpsest.) The term came to have an important metaphorical meaning in the modern period when Pound and H.D. began to suggest that the word could also signify the many layers or meanings still recoverable “underneath” a particular text or phrase. The idea behind such a metaphorical usage is that language, like a “writing surface,” has been used over and over again, therefore, it must somehow bear the traces of its former uses.

Eliot’s work can be typified as a palimpsest because it seems to bear multiple meanings that can be recovered if one looks “underneath” the text. This is most clearly evident in his constant allusions and references to former works of art. The Waste Land is informed by the myth of Aeneas, the Grail legend, and by significant references to Dante’s Inferno and the drama of John Webster (among other writers).

The new metaphorical meaning of palimpsest also informs one of Eliot’s most significant essays, “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” In this work, Eliot contends that “universal” works of genius (“individual talent”) are constantly being added to the core of world literature, thus they are constantly in dialogue with and revising “tradition.” This dialogue, though, goes both ways. Although Eliot did believe that authors could “make it new,” he was also more than aware of the ways in which previous writings and previous tales necessarily inflected modern works. Any writer who partakes in the “Tradition” can thus help to resignify that tradition, but the “Individual Talent” will also bear the traces of the writing that came before.