The Romantic period in English literature (~1789-1832) is typified by the spirit of REVOLUTION. Romantic individualism was forged in the midst of political unrest.

The Industrial Revolution (IR): The IR neither begins nor ends with the Romantic period, but some of the greatest political and philosophical debates about the merits of industrialization occurred during the Romantic era, which saw land being enclosed and factories being built at a rate unprecedented in history. For the most part, Romantic writers rejected the aims and ends of the IR and favored a return to “simpler” times and more agrarian ways of life. Byron’s support of the Luddite Rebellion in the House of Lords, Blake’s vituperative attack on the “dark satanic mills” that were despoiling the countryside, and Wordsworth’s celebration of “Humble and rustic life” are all examples of the Romantic disavowal of industrial “progress.”

The French Revolution: Like the rest of Europe, Britain was galvanized by the French Revolution. For Romantic writers, the storming of the Bastille demonstrated that oppression could be vanquished through a collective will to act and that cataclysmic change could be brought about through the philosophical focus on individual liberty and equality. Although many Romantics would distance themselves from the politics of France after the Reign of Terror and the rise of Napoleon, they remained committed to the ideas that animated the early days of the Revolution. Many Romantic works of art contain literal or symbolic references to the French Revolution; our primary concern will be with Mary Wollstonecraft’s Revolution-inspired “Vindication of the Rights of Man” and “Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”

Poetic revolutions: Reacting against what they perceived to be the Augustans’ slavish devotion to classical forms, Romantic writers advocated a liberated method of expression that privileged the emotional honesty of artistic content above the technical difficulty of the method of expression. This impulse finds its fullest and clearest articulation in Wordsworth’s Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, but it is also evident in Coleridge’s theories of organic unity, Barbauld’s paeans to “common” experiences, and Mary Robinson’s sonnet cycles and later verse. As Robinson’s, Barbauld’s, Coleridge’s, and Wordsworth’s work shows, Romantic writers exhibited both technical accomplishment and innovation; they just rejected the notion that poetry could only be about certain seemingly elevated subjects or utilize certain prescribed forms.

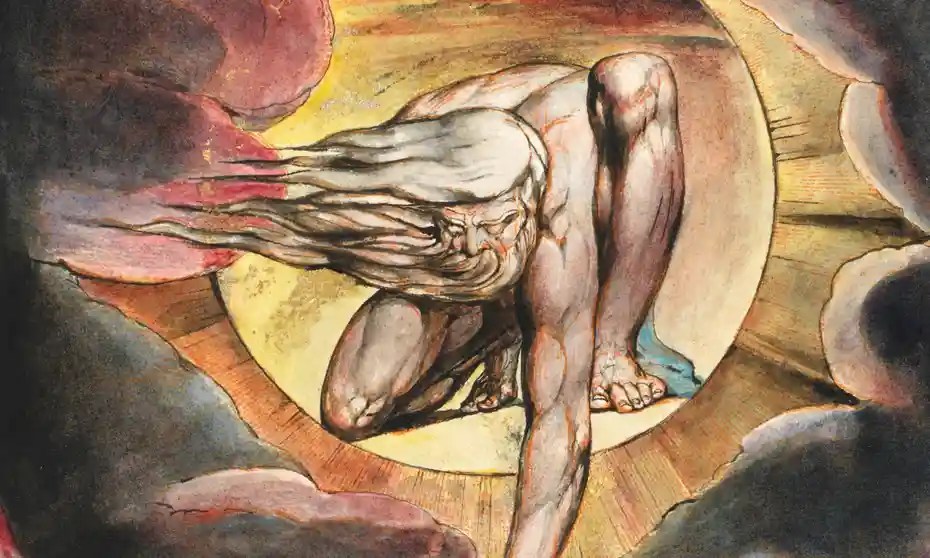

Scientific revolutions: While Romantic works like Frankenstein and Blake’s painting of Newton display a real wariness of unchecked materialist philosophy, it would be a mistake to read these critiques of the potential excesses of Enlightenment thought as a rejection of scientific progress and discovery. Keats may have noted that “cold philosophy” could unweave a rainbow and clip and angel’s wings, but such notations merely recognized that science alone can not answer all the questions of life. Many Romantic thinkers, like Barbauld, were fascinated by scientific discoveries, as these discoveries often showed the complex interconnections of life forms and the possibility of progress and change. (A few notable discoveries are: Jenner’s small pox vaccine [1796], the electric battery [1799], Dalton’s atomic theory [1808], Farraday’s work with electromagnetism [1821-on], and Non-Euclidean geometry [1829].)

These revolutions are manifest in Romantic literature through the authors’ use of recurrent themes:

- Primitivism: Following Rousseau, Romantic thinkers focused on the positive elements of a “natural” education, decrying the deleterious effects of civilization and advocating a return to more fundamental states of cultural innocence. In addition to valorizing the concept of childhood (Wordsworth famously remarked that “The child is the father to the man,” while Barbauld demonstrated how the “sport of children” prefigures the most advanced “toils of men”), the Romantics advocated a return to an historical past when humanity was not so removed from its “natural” state (such thinking is advocated in Wollstonecraft’s political discourse, which defines the “natural rights” of men and women, and it is also evident in Wordsworth’s preference for being a “Pagan suckled in a creed outworn” over a modern man divorced from the elements of nature).

- The Medieval Revival: Celebratory references to the medieval period served a dual function in Romantic thought. The so-called “Dark Ages” signaled a time before the “progress” of the Industrial Revolution and epitomized a thorough rejection of the artificiality of classical order (hence it served as a rejoinder to the Augustan’s classical revival). As the Romantic painter J.H. Fuseli argued, “We are more impressed by the Gothic than by Greek myth, because the bands are not yet rent which tie us to its magic.” These bands are literarily evident in Gothic works such as Keats’ “Eve of St. Agnes” and Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” (Fun fact: the name of the period itself is derived from the medieval romance.)

- The Imagination: All creative works, by their very nature, privilege the imagination. The Romantics are notable for highlighting the role of the imagination in the creative act and for privileging this creative capacity as another way of knowing. Enlightenment thinkers had demonstrated what could be learned from empirical observation alone. Romantic thinkers augmented this insight with the imaginative perception needed to “investigate” intangible issues, ideas, and entities. For this reason, many Romantic texts focus on dreams and visions, and some of the most famous poems are examples of “excursion and return,” or works that dramatize the intellectual and emotional insight gained by a speaker through the process of imaginative journey (see for reference Barbauld’s “Summer Evening’s Meditation,” Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” and Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”).

- Nature: Like countless artists before them, Romantic thinkers focused on the beauties of nature. Their specific focus, though, was designed to counter the damaging effects of society’s cultural “errors” (the mechanization of industrialization, the conceptual limitations of narrowly conceived scientific progress, the tyranny of oppressive forms of government). Nature, for the Romantics, was less a pleasing object to be faithfully reproduced in art than a potent force to be symbolically registered in aesthetic and political arguments against limited, materialist thinking. In Romantic poetry, “natural” elements, like the west wind or a simple nightingale, become symbolic markers of revolutionary change and eternal spirit.

- Individualism: At its core, Romantic writing is a celebration of the self. Whether they are vindicating the individual rights of men (and, to a lesser extent, women), declaring the poet to be a “man speaking to men,” or celebrating the divine individuality of experience, Romantic writers are valuing the inalienable singularity of the self. Like the framers of the American Constitution, and the early thinkers of the French Revolution, Romantic writers believed that a good society is guaranteed through the preservation of the “natural” rights of individuals. They also believed that art could only be created by an individual (and individualized) consciousness, which is why so much Romantic literature tends to focus on the speaking self.

- The Sublime: Speaking of the self, Romantic literature is also informed by theories of the sublime. These theories are not strictly coeval with the Romantic period, but the Romantics built upon elements of the sublime (the experiences of almost incomprehensible vastness and greatness, a contemplation of the seemingly irrational) and articulated a sublime aesthetic that fit well with other Romantic preoccupations. During the Romantic period, the sublime became associated with an appreciation of irregularity and disorder (hence with an appreciation of the medieval and the “dark” forces of nature) and became a function of the perceiving self (in line with the focus on individualism, the sublime was seen as an experience created within the viewer/thinker, not a quality inherent within the object/idea being contemplated).