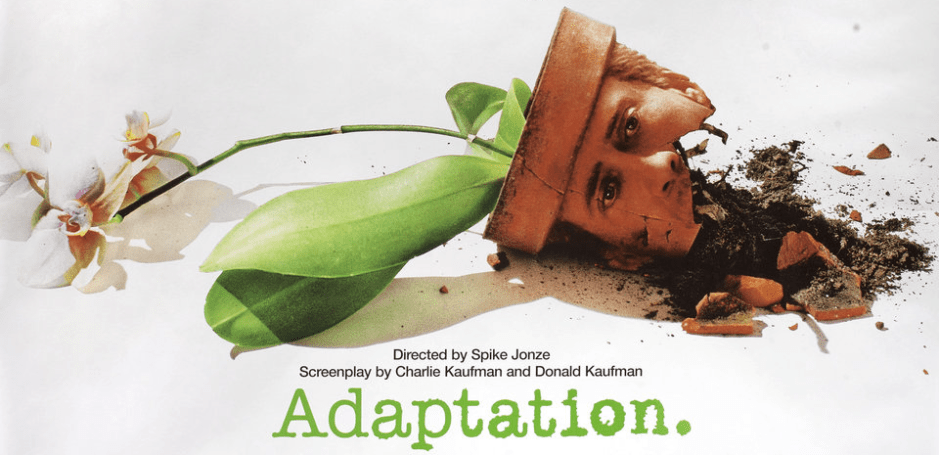

Adaptation, Art, and Authority

Early discussions of the artistry of film fell into polarized debates: Detractors contended that it was a technological marvel meant to amuse the masses, whereas defenders vaunted cinema’s unique ability to reorganize space and time through pictorial representation. In other words, people tended to see movies as either a derivative medium that could, at best, reflect a “real” art form (e.g., in the film recording of a stage play) or a “pure” form of art with its own signifying systems, methods of representation, and, indeed, language.

Both arguments have their fair share of merit in studies of adaptations (many serious films are adaptations of traditional forms of art such as plays, novels, and short stories, while techniques such as lap dissolves, montage, dutch angles, and shot-reverse-shot sequences suggest that “the medium is the message“), but many current critics, following in the wake of Sergei Eisenstein, like to think of film as a syncretic form that draws upon established art in order to achieve its own spectacular effects.

Flickering shadows on the wall

As Maya Deren argues in “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality” (1960): “The motion-picture medium has an extraordinary range of expression. It has in common with the plastic arts the fact that it is a visual composition projected on a two dimensional surface; with dance, that it can deal in the arrangement of movement; with theatre, that it can create a dramatic intensity of events; with music, that it can compose in the rhythms and phrases of time and can be attended by song and instrument; with poetry, that it can juxtapose images; with literature generally, that it can encompass in its sound track the abstractions available only to language” (p. 152). This seeming amorphousness, Deren contends, is part of what allows motion-pictures to be “capable of creative action on [their] own terms,” because the cinematic form can (re)combine other artistic media in its own particular visual language.

In order to seriously discuss a filmic adaptation, we have to start from the assumption that the admitted “mechanical reproduction” is offering a *new* version of the work in a different medium. Then and only then can we begin to judge what that admitted reproduction is doing in and through its own artistic medium.

Just Picture It: Camera Work

Like its early precursor, photography, film has been alternately praised and reviled for its ability to capture “reality.” Yet moving pictures, like static photographs, are never merely transparent images of reality created in and through scientific innovation. Artistic vision and technical skill are needed to take a picture that people consider worth viewing.

This point is manifest in the fact that scholars distinguish between photographic and filmic works that are merely records of events (historical verification) and other works that embody a particular aesthetic. Consider, for example, how we treat the “Burning of Atlanta” scene in Gone with the Wind differently than we treat footage of an actual fire, or how we appreciate “The March of Time” in Citizen Kane in a way we would never appreciate a genuine newsreel from that era. Artistic photographs are studied for their composition and technical skill; artistic films (which are often narrative) are studied for their mise-en- scene, camera work, editing, and use of sound.

For all filmmaking and photography have in common, there are some important differences. Film, which would not exist without the photographic image, adds the important dimension of movement to the artistic equation. Although people rarely refer to “moving pictures” anymore (opting, instead, for either “movies” or “pictures”), it is undeniable that the “moving” form is defined through its sequencing and pacing of individual stills. Photographers, of course, can place images next to one another, superimpose, and even demonstrate collage and photographic sequences, but they cannot control the order of the images, nor the ways in which the audience takes those images in, in the ways that a projected film can. Film also tends to be a much more of collaborative art than photography. A photographer with a lone camera can achieve his/her artistic ends; a lone filmmaker cannot be the director, actor, cameraperson, and every other “helper” (although Tyler Perry does try).

A Collaboration of Coagents

Because film is such a collaborative form, it is impossible to pinpoint who (or what) is fully “responsible” for the final work of art (cinema could even be said to be shaped by the person who projects it in a theatre). That impossibility, though, doesn’t stop most of us from trying. Film may not be “celluloid recollected in tranquility,” but many scholars and critics have attempted to render a singular Romantic artist out of the cast, crew, and spectators. Listed below is an overview of the “usual suspects.”

Author, auteur

Most film critics and scholars tend to refer to films by directors because they assume that the director is the person with the most control over all aspects of the film and its production. (This is the reason the “Best Director” Oscar precedes the “Best Picture” at the Academy Awards ceremony.) This focus is critically reinforced by the “auteur theory,” or the polemical contention that certain directors (such as John Ford, Orson Welles, or Alfred Hitchcock) imbue their work with such a personal style and vision that it is best to think of their films as creations of a gifted “author.” Formulated by Francis Truffaut and popularized by Andrew Sarris, the theory continues to generate much discussion, particularly because it fails to acknowledge that good directors can create bad films (and vice versa) and seems to elide the contribution of the screenwriter and other collaborators. Still, in common parlance, the director is often viewed as the controlling artist of film.

Stars, ready for a close-up

If critics have privileged the role of the director, the public has valorized the role of the star. Ever since Carl Laemmle named the “Biograph Girl” as part of a publicity stunt, the public has responded to the marketing of individual talent in the “star system.” While many stars have contributed immeasurably to the artistry and brilliance of celebrated films, rarely are they responsible for the other actors, the script, the cinematography, and the editing—key elements that must combine to make a truly great film. (Charlie Chaplin is the obvious exception here.) In other words, Norma Desmond may have “built” Paramount studios, but she still needed Mr. DeMille to give her a close-up.

A “System”-atic art

“Universal Studios” may not have the Romantic appeal of the brilliant James Whale or “Karloff the Uncanny,” but there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that movie companies contributed much to many classic Hollywood films. During the so-called “studio system,” it was the movie companies that determined what stars acted in which movies and what projects directors could begin. More often than not, the final cut of a movie was reserved not for the director, but for the studio. (Although the days of the big studios are over, some things haven’t changed. It may not be the equivalent of the butchering of The Magnificent Ambersons, but the voice-over narration in Blade Runner was obviously the choice of the studio—not the resistant star or director.) Given the fact that many films can be identified by their studios, even without recourse to the logos and opening credits (such as “an MGM musical”), it seems logical that studios should factor in to these discussions.

And the support of viewers like you. . .

Last, but not least, is the viewer. Much more so than any other art form, film production is determined by what sells, so movie-goers are themselves implicated in the creation of movie art. (For example, there would be no genre of “film noir” if it people had not gone to see movies in that style.) Also, film in general, and classical Hollywood in particular, was never viewed as a serious art form until a group of French critics in the mid part of the century began making aesthetic claims for popular works that many Americans took for granted. The French are obviously fallible tastemasters—as their love of Jerry Lewis demonstrates—but they did appreciate Orson Welles long before we did. If it were not for interested viewers, we would have neither recognizable film forms nor institutions dedicated to the preservation of film history.