Syncretism and Adaptation

In “Ways of Seeing,” I outlined the various approaches instructors could take in a literature and film course, but even that brief overview limits what can be considered in terms of adaptation. Analogy, borrowing, or loose adaptation is by far the most common form of adaptation, and not all textual intersections are literary based. (Placing an adaptation course in an English program is in and of itself a constraint, and that’s even before a given instructor makes individual decisions based on “literary merit.”) The messiness of Jonze’s Adaptation (2002) is actually more typical of textual transformation than the decorous stitching of Langton’s Pride and Prejudice (1995), and that is rarely captured in English Studies.

One need only look at the long-running animated series Family Guy‘s parodic treatment of “The Shawshank Redemption” to see the process of adaptive transformation includes far more points of input than most staid studies acknowledge:

Paul Wells’ “Classic literature and animation: all adaptations are equal, but some are more equal than others” and Peter Brooker’s “Postmodern adaptation: pastiche, intertextuality and re-functioning” (chapters 13 and 7 in The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen) provide us with with critical terms that can explain the multiple intersection here, but we cannot successfully apply the “subjective correlative” or ponder “refunctioning” if we fail to privilege syncretism over source.

Depending on your point of view, this particular artifact may or may not be worthy of consideration. I don’t find it particularly noteworthy myself, even as a Family Guy episode. Were I not interested in issues of adaptation, I’d probably just dismiss the entire thing. The clips are provided here, though, because the finished product (almost painfully) foregrounds the process of recombination (we can see the constitutive parts yoked in each obvious joke). The very loose adaptation is not good, but it is illustrative. And this illustration offers a way to begin addressing processes and principles of adaptation.

As Kamilla Elliott argues in “How Do We Talk about Adaptation Studies Today?,” “we rarely discuss adaptations as adaptations: instead, we discuss them as books, films, and other media; as history, aesthetics, politics, economics, psychology, sociology, and philosophy, and place them in the service of battles over value and ideology. Too much energy has gone into debating which principles should govern the field and not enough into locating and debating principles of adaptation” (para 5).

I would never suggest that I am locating these principles, or fully focusing on adaptation as adaptation (I’m more allied with the empiricism of Linda Hutcheon than the meta-adaptation processes that interest Elliott), but I do understand the “writerly” impetus of Thomas Leitch’s Film Adaptation & Its Discontents. As he rightly notes, “texts remain alive only to the extent they can be rewritten and to that experience a text in all its power requires each reader to rewrite it” (p. 12-3). The fact that I have, and will continue to treat “source texts as canonical authoritative discourse or readerly works” (Leitch p. 12) in my English classes does not mean that I am insensitive to the need for writerly engagement overall.

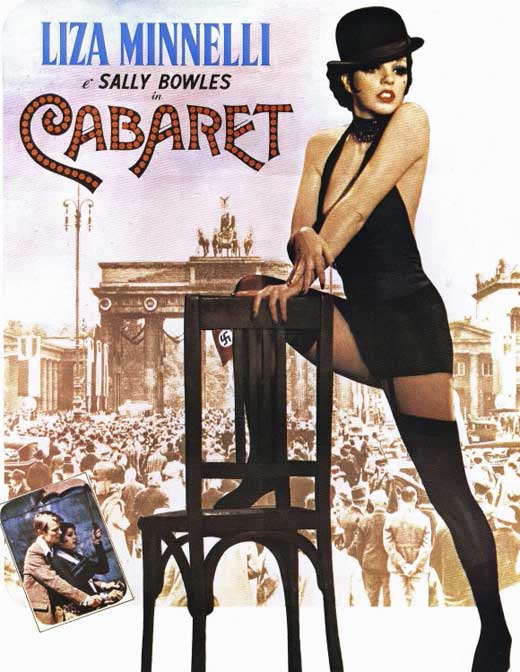

Many texts in my main area of study (20th-century British literature) have only remained “alive” because they have been “rewritten” by readers. Take, for example, Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin (1939), a poignant work published at the end of the “low dishonest decade” that ushered in what Holman and Harmon term the “diminishing age of English literature.” Crafted into a Broadway play (I Am a Camera [1951]) that would be turned into a musical (Cabaret [1966]) that was filmed in 1972, the episodic work remains a cultural nodal point precisely because the biographical text has been refashioned in so many ways.

That said, “Cabaret” (1972) is more than just a prop for a second (or third) tier work. The literature here is like one of the chairs in Liza Minnelli’s “Mein Herr” performance: a source of support, for sure, but one that can be moved and rearranged in stunning choreography for new effects. The brief outline below doesn’t move beyond case study (as I already noted, I’m allied with the empiricism of Hutcheon), but it does show why even unrepentant readers (like myself) can and should appreciate a “writerly” praxis that begins to explain the principles that undergird such pleasing effects.

Fosse’s film lies somewhere between adaption and allusion in relation to Isherwood: It is a treatment of a musical that was itself based on the novel–so many levels removed from the purported “origin.” While the film is widely praised, it is not a product of a “tradition of quality” in cinema, not in the least because Fosse’s fame rests on his achievements on stage. It is, quite rightly, its own entity, one indebted to the star presence of Minnelli. And this presence provides its own intriguing meaning. The character of Sally Bowles is framed in this film (as she is in the novel and musical) as a “mediocre” singer. The jarring juxtaposition between that frame and the bravura of Liza Minnelli’s performance (for which she rightly won an Oscar) creates its own dissonance, one that reorients what is “second rate” and a “delusion” in the diegesis. Arguably, the film–which foregrounds the contradiction of the “middlebrow“–is more modernist than Isherwood’s materialist tale.

No one is trying to turn the vinegar to jam here. The initial connection to Goodbye to Berlin was a fine affair, but now it’s over. Fosse’s film (and Minnelli’s performance) does what it does, and when it’s through, it’s gloriously through.