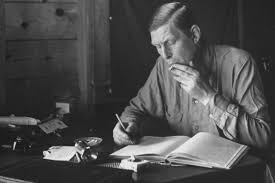

W.H. Auden came of age when High Modernism was coming to an end, and he completed some of his most innovative work when America was on its way to becoming a political as well as a cultural superpower. Even though a great deal of his work carries on where the High Moderns left off, his shift to a “conversational style,” coupled with his interest in politics (and interest would abandon), is often used as an excuse to render him part of a Movement away from modernism itself.

(Danny Heitman’s “The Messy Genius of W.H. Auden,” in HUMANITIES, the magazine of the National Endowment of the Humanities, offers a tidy summation of the poet’s chaotic literary classifications.)

A Generation Past (High) Modernism—the “Pylon School”

Samuel Hynes titled his influential study of Auden “The Auden Generation” for a reason. The poet was fairly typical of his “generation”—a generation of young men who grew up idolizing men who has served in the First World War—and he was the most dominant poetic voice of this post WWI generation. As Hynes notes, Auden’s connection to and influence over other English writers of the 1930s made him a paradigm of the decade. Studies of Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender, Louis MacNiece, and Christopher Isherwood rarely fail to mention Auden and his influence, and Auden is often understood in and through his poetic influence over others. Although the “Auden Generation” has come to be the most common classification of the group of writers that clustered around Auden, these young poets of the 1930s were originally dubbed the “Pylon School” because they seemed to incorporate and even celebrate modern mechanical and commercial marvels in their poetry. In this way, there were very unlike the High Modern poets of the 1920s who eschewed the mechanization of life.) According to David Perkins (author of A History of Modern Poetry) Auden and other poets of the 1930s “wrote of automobiles, jazz bands, diabetes, and hair oil as familiarly and casually as if they were sunsets and daffodils, and thus took final possession of the modern scene for English poetry.”

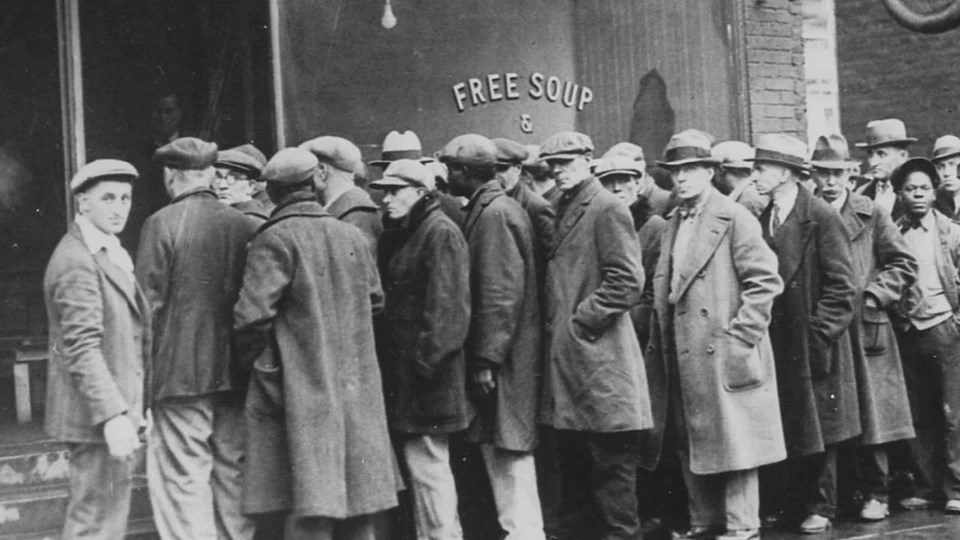

Politics and the “Low Dishonest Decade”

Auden began his poetic career during a very “political” decade. The 1930s were a time of rampant depression, socialist agitation, international reactions to the civil war in Spain, and increasing moves toward fascism in many countries. Many writers who came of age during this time in Britain were affected by these international events, and they often sympathized with what could loosely be termed a “Marxist” position. Auden himself participated in the Spanish Civil War (as a civilian radio correspondent), and he wrote many lyrics about the troubles in Spain. Some critics use this evidence to argue for Auden’s “socialist” credentials (or at least his interest in left-leaning politics), seemingly despite the fact that the author later refused to reprint many of those poems and famously declared, in poetry as well as prose, that “poetry makes nothing happen.” (Auden’s apparent “politicization” of verse is another factor that would seem to remove him from modernist aesthetics.)

He DO the Moderns in Different voices

Auden is both celebrated and censured for his conversational style. Those who praise his “prosy” verse note how his work is able to loosen and play with the formal constraints that restricted even Yeats’ magnificent rhetorical style. Those who question his over-reliance on “talk” argue that his work is often too glib, impressionistic, and facile. (Although these critics rarely use Auden’s own critical words to damn him, they would argue that his ear has been “corrupted” by the degradation of modern language.) Whether figured positively or negatively, Auden’s “talkative” style is his most characteristic poetic trait, one that effectively differentiates even his American verse from the dominant school of Imagism. Auden may condense images (and rely often on synecdoche), but he rarely prunes away excess words or seemingly superfluous figurative language. Whether or not they adopt his prolix style, many contemporary poets build upon the poetic “conversations” Auden began, using this seemingly more informal style was a way to introduce topics that had not yet been broached in poetry.

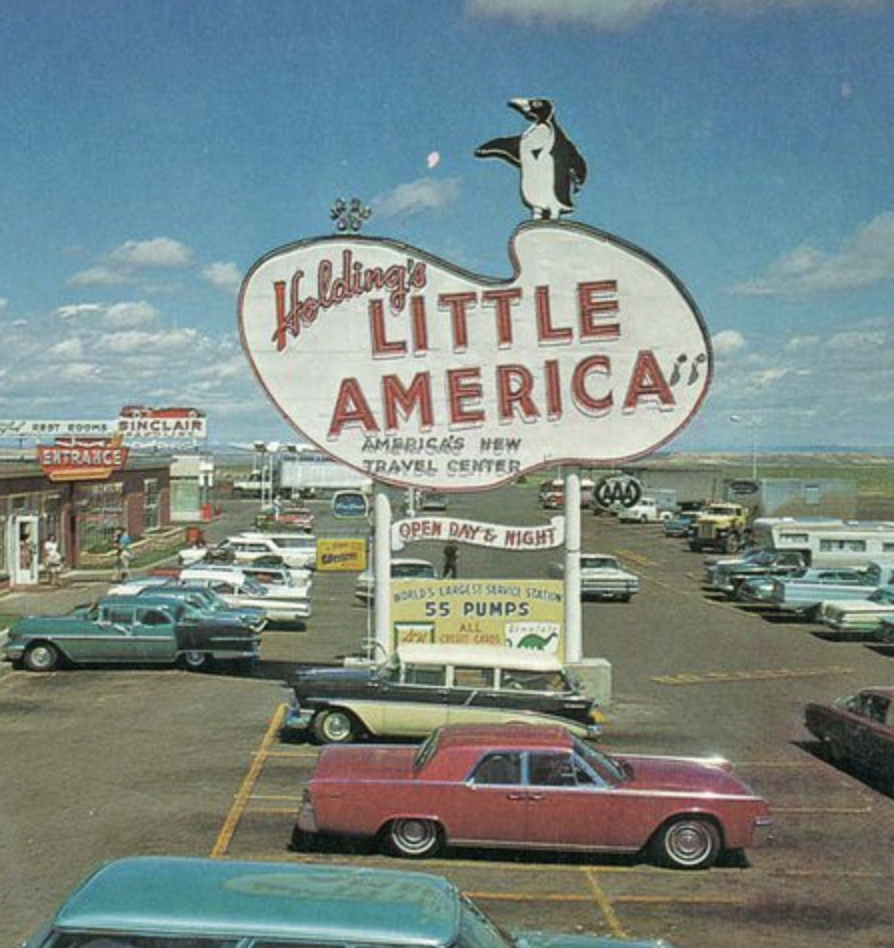

The Age of Anxiety—Auden Moves to America

In 1939, perhaps in response to the events of September 1st, Auden moved to America. His English contemporaries including the rest of the “Pylon School,” may have felt a bit betrayed, but the immigration did not affect his poetic sensibilities. He continued to make references to England, and his work retained its distinctly cosmopolitan themes and messages. The Age of Anxiety (1948), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, manages to convey a generally “modern” condition in and through the conversation of four unlikely compatriots in a New York City bar. Like the one established poet who would hail The Age of Anxiety as Auden’s best work to date, T.S. Eliot, Auden eschewed the idea of a strict national identity, fashioning himself as a citizen of the world. Even though some critics are fond of speaking of an “English,” “American” and even “Austrian” Auden, the author is best understood as an English language writer whose rootlessness or multiple connections (depending on your point of view) fueled his creativity.

This rootlessness, though, is not given the same critical approbation as that of his Modernist predecessors. Seemingly despite that fact that no one is able to understand an “English Auden” without somehow including the “American Auden” as well, critics have continued to make unwarranted national distinctions, particularly in regards to the author’s creative powers. Some contend, with precious little evidence, that the transplantation signals a waning of creative powers (a point most often made by British critics) whereas others somewhat uneasily place him in a second or third tier of American poets. (He’s a frequent fixture of scholarly websites on American poetry, but he doesn’t tend to make it into anthologies devoted exclusively to American poetic work of the 20th century.) Whereas American expatriate writers of the early 20th century are lauded for their travel, and celebrated for their engagement with cosmopolitan themes, the immigrant Auden is often indicted for his movement and critiqued for his seemingly glib sentiments on world issues. As the following will show, this isn’t terribly fair, as Auden is actually carrying on many of the important thematic and stylistic concerns of High Modernism while he paves the way for the “Confessional” style of poetry that will revolutionize contemporary American verse.

What Might the Anomalous position of Auden say about a Moving Modernism?

If Eliot’s (and Pound’s) movement from America to England in the beginning of the 20th century partially demonstrates the “cultural capital” England held during the Modern period, then Auden’s move (in 1939) from England to America gestures toward England’s slow aesthetic and cultural “decline” during and after WWII. Critics still debate whether Auden’s individual emigration was opportunistic, but it is undeniable that modern aesthetics found a more ready home in America during WWII and the immediate postwar period than they did in England. While American artists were following up on modern aesthetic innovations, many English poets and writers were rejecting modernist ideals and looking to 19th-century authors for artistic inspiration. Well-publicized poetic schools, like the Movement, seemed to lend credence to the fact that English literature was in a “Diminishing Age” (a periodizing phrase for English literature of the postwar period used in the most cited literary handbook, Holman and Harmon’s), and the canonization of Sylvia Plath as a specifically American poetic phenomenon all but seals the deal. (Only in the context of the decline of English literature and the rise of American innovation could an American poet who married a prominent English writer and wrote most of her important verse in England be considered wholly American in word and deed.) Auden’s move is so important because it seemingly recapitulates the history of modern poetry in the 20th century.