“Hooked on Explication” offers an illustrated overview of how to write about literature. Below is specific compositional advice that can aid the drafting process. Use this wonderful work (courtesy of Dr. Sarah Morrison) to review your own writing.

The form of the essay

Title:

- Your title should point to the issue addressed and your stance on the central question.

Introduction:

- Mention the author’s full name and the full title of the work (or works) you will discuss.

- Introduce the problem or question you will be dealing with.

- Briefly acknowledge other possible critical stances.

- Take your stand: state your thesis (i.e., your position on this issue). [To test your thesis: make sure that it is a significant enough point to argue and that there are several other defensible positions that one could reasonably hold.]

Body of essay:

- Here you will develop a reasoned argument through a series of points that support your thesis. You should employ evidence from the primary text and from critics’ published critical arguments.

- When you quote from the text, remember to include parenthetical citations with page numbers for prose works and line numbers for poems.

- It is generally NOT a good idea to follow the chronology of a narrative or plot in developing one’s argument. You should organize your essay around the key points that you are making about the work: you should anticipate that each of these points will generate a paragraph with a distinct focus.

- Keep plot summary and paraphrase at an absolute minimum, using only as much as you actually need to illustrate and support your claims. Remember that you should assume your audience knows the work well. (Think of readers who know the work as well as you do but who read it differently.)

- Employ transitions and phrasing throughout that will tie the various points you make into the thesis that you stated at the beginning of your essay.

- As with any argument, you should anticipate and respond to challenges likely to come from resistant readers. (Again, think of those readers who would have a very different answer to the question you began with.)

Conclusion:

- Reassert your thesis and extend your claims to underscore the significance of the issue you treat here to an understanding of the work as a whole.

Works Cited:

- Both the primary text(s) and outside sources used in your paper must be listed on a properly formatted (i.e., MLA style) works cited page. Keep in mind that a “works cited” page is different from a “bibliography of works consulted”: Do not include works that you looked at but do not actually make use of in your paper.

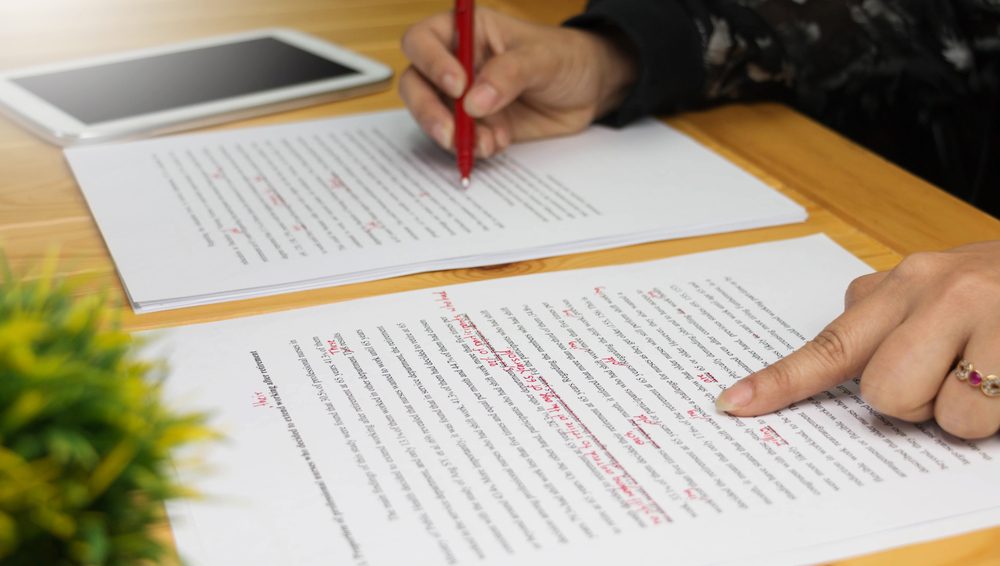

Transforming your draft

Remember that the first draft will be a process of exploration. You will discover your thesis as you write. Only after you have figured out what your thesis is will you be able to organize, focus, and develop your material into an effective argument. Expect to—

- re-order points

- cut big chunks of your draft

- pare down and condense paraphrase, summary, and quotation

- adjust the phrasing and emphasis throughout

Your goal should be to keep the central question before the reader and to make it easy for readers to see the relevance of every point you make along the way.

Make sure that you define the critical issue and state your thesis explicitly very early in your paper. It will help to ensure that your thesis is significant enough to support an argument of this length, and it will help you maintain the focus and avoid wordiness and padding.

If stating your thesis early makes you feel as if there’s little left to say, it is possible that—

- You really are not working with a significant enough point: if this is the case, you need to push your thinking further to come up with a stronger thesis.

OR

- You are erroneously assuming that a point that needs to be argued is self-evident: if this is the case, you need to consider all the objections and tough questions that might come from a tough, resistant audience and reshape your argument to address these issues.