Generic Transformation and Adaptation

Filmmakers have adapted works of drama, fiction, and poetry. Each of these major genres presents its own possibilities (and potential limitations).

From stage to screen

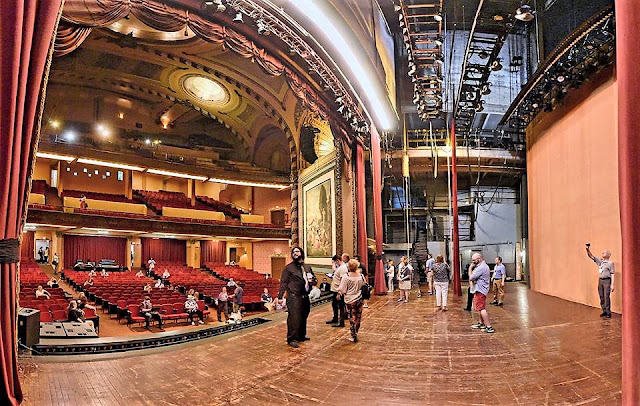

Theatre and film have much in common, and not merely because each relies on the seemingly non-literary elements of actors, sets, props, and directors. In the early part of the 20th century, film was viewed as a rival to theatre (just as television in the 1950s would be viewed as a competitor with film). Not only did theatre practitioners view the film industry as its rival for talent (both acting and directing), but the theatre industry also saw film as cheap (and imitative) substitute for plays. The fact that much Hollywood cinema relied (and continues to rely) on structures formulated in the “well-made plays” of the 19th century did little to ease the tension. Although there is still some grumbling about the popularity of movies, both theatre and film practitioners soon learned that “canned” productions of plays were advantageous to neither medium. Audience members that want a stage experience still go back to the theatre, and those that want to see a movie go back to the cinema.

The last statement may appear a bit ironic (or even misinformed) considering the fact that many celebrated films are adaptations of plays that star stage actors. The two most obvious examples are Olivier’s Henry V (1944) and Kazan ‘s Streetcar Named Desire (1951, a film that starred all of the original Broadway cast save Jessica Tandy). Neither one of these films, though, is a canned performance—and not just because the censors made Kazan subtly change the end of Williams’ play. Both films exploit space in a way that the stage productions never could. After some opening shots that locate the viewer in the Globe theatre for an Elizabethan production of Shakespeare’s play, Olivier widens the setting and scope by moving his spectators onto the field of Agincourt. Kazan is able to literalize William’s metaphorical streetcar by showing Blanche (played by Vivien Leigh) riding “Desire” to her sister’s house.

As André Bazin notes in What is Cinema? (Volume I), filming a play “can give the setting a breadth and reality unattainable on the stage” (p. 86). More than just offering an added surplus of views and vistas, this increased breadth gestures toward one of the ways in which film and theatre differ. According to Bazin, “The human being is all-important in the theatre. The drama on the screen can exist without actors. A banging door, a leaf in the wind, waves beating on the shore can heighten dramatic effect” (p. 102). This is anti-corporeal element is even evident in the very human (and physical) focused Streetcar, when the broken mirror comes to symbolize Blanche’s complete descent into madness.

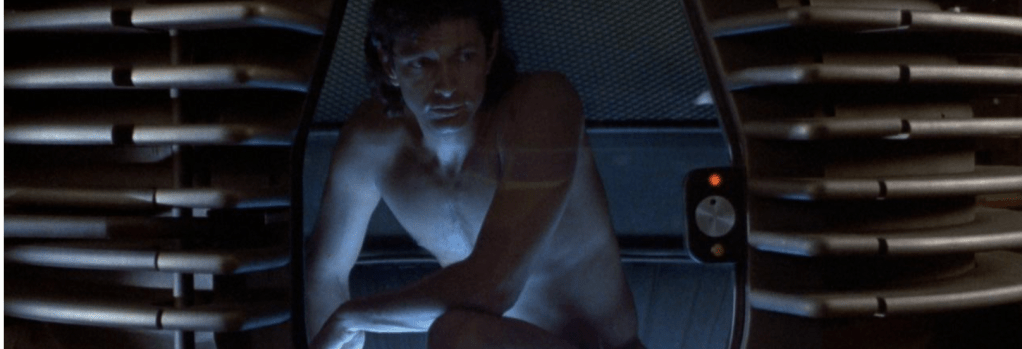

In addition to placing more focus on the “décor,” narrative film also necessitated a shift in acting. Broad gestures and heavy make-up visible to even the furthest reaches of the auditorium were soon to be replaced by subtle facial expressions and slight movements. While the acting in silent movies may appear overtly dramatic to a contemporary viewer, it really did offer a new method of expression that relied on minimized gestures of the body rather than voice or large gesticulations. This, of course, is not to say that there were not bad silent actors—there were. This is only an acknowledgement that the technology of film, which offered actors something they had never had before—a close-up—afforded many fine stars a chance to achieve reality effects never seen before.

The process of rehearsal and performance is also different for actors on film. Stage actors are able to rehearse scenes in relation to one another and rework their performances as a whole each night. Most importantly, they are able to gauge themselves in relation to the audience and audience reaction. (This is the “liveness” that so many theatre critics and practitioners praise and celebrate in theatrical productions.) Screen actors have no such liberties. Often, they must repeat scenes so that the camera can take them from different angles, and they must come in where and when they are needed. Directors and editors are the ones who control the “whole” of the finished product in film—actors, who are brought in, used, and filmed, are not.

A novel idea

The novel, particularly the 19th-century realist novel, had a profound impact on the film industry. As Timothy Corrigan notes in Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader, “theatrical structures seemed originally most suited to the stationary camera of early cinema, [but] the development of editing techniques and camera movement pointed the cinema more and more toward the mobile points of view found in the novel” (p. 15). The work of D.W. Griffith is an excellent example of this “pointing.” The melodramatic plots of Griffith’s greatest works (such as Broken Blossoms) may have been borrowed from the theatre, but his method of narration was indebted to the novel, particularly to his love of Dickens. As Sergei Eisenstein argues in “Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today,” Griffith’s “limited” form of montage, circumscribed primarily to parallel editing, is itself a structural equivalent (or cinematic adaptation) of Dickens’ narrative techniques.

While the primary difference between film and theatre may be the idea of “liveness,” the fundamental distinction between film and the novel is representation: “Where the novel discourses,” George Bluestone asserts in Novels into Film, “the film must picture: (p. 47). This difference is strikingly evident in filmic adaptations of novels, which must do more than just condense and streamline the story into a two-hour digestible narrative. As Seymour Chatman relays in “What Novels Can Do That Films Can’t (and Vice Versa),” film necessarily offers viewers a plentitude of visual details, but it cannot prioritize and control those details as the novel can. According to Chatman, this lack of prioritization is primarily a function of film’s inability to seamlessly “stop” and add selective description.

To use one of his examples, Dickens can stop the action in Great Expectations as Magwich grabs Pip in order to describe the terrifying convict from Pip’s point of view. This description momentarily arrests the narrative and creates dramatic suspense. A filmed version of the scene, which would already offer the viewer a material representation of Magwich on the screen, could not pause this moment for effect without somehow signaling that time has stopped for Pip or drawing attention to the artifice of the medium. This “inability” explains the narrative choices of David Lean’s famed scene:

As with photography, the key difference here is movement. The film version may be able to offer more visual details than Dickens could ever dream of, but, in order to keep the narrative going, the images have to move at a pace that rarely allows a viewer to analyze most of what is in the mise-en-scene (unless, of course, the viewer is watching a tape or DVD that s/he pauses every other frame). In other words, filmmakers must deal with the contingencies of time in narration in a way that novelists will never have to.

If films are limited by time, though, novels are limited by a sense of space. Just as novels can move backwards and forwards in a sense of time, so films can revel in space and spatial depiction. Dickens may be able to play with the time it takes a reader to digest his work by purposefully elongating some scenes and telescoping others, and he may be able to seamlessly subvert chronology by manipulating the temporal sequencing of the plot (e.g., he could tell us of Pip’s first days as a gentleman before he finishes the scene in which Magwich grabs the poor young child), but he cannot render the full array of space and location around Pip without destroying his narrative continuity. A film version, in contrast, can offer a wide variety of vistas and a great deal of background “description”/depiction instantaneously, but it cannot stop in order to describe a specific aspect within an event without drawing attention to itself, or shift the time within the narrative without obvious transitional devices. As Bluestone suggests, “The novel renders the illusion of space by going from point to point in time; the film renders time by going from point to point in space” (p. 61).

These important differences highlight the fact that even when a film and a novel have the same storyline, they are necessarily different entities. Nowhere is this more evident than in the area of narration, where seemingly amenable narrative forms, like first person narration, must be subtly refashioned in order to work on film. The camera is omnipresent in film, and this de facto narrator will always provide a visual element to the tale. Notice, for example, how Neff’s story must necessarily “morph” into a seemingly third-person account in between the scenes of the agent at his desk for Double Indemnity to work:

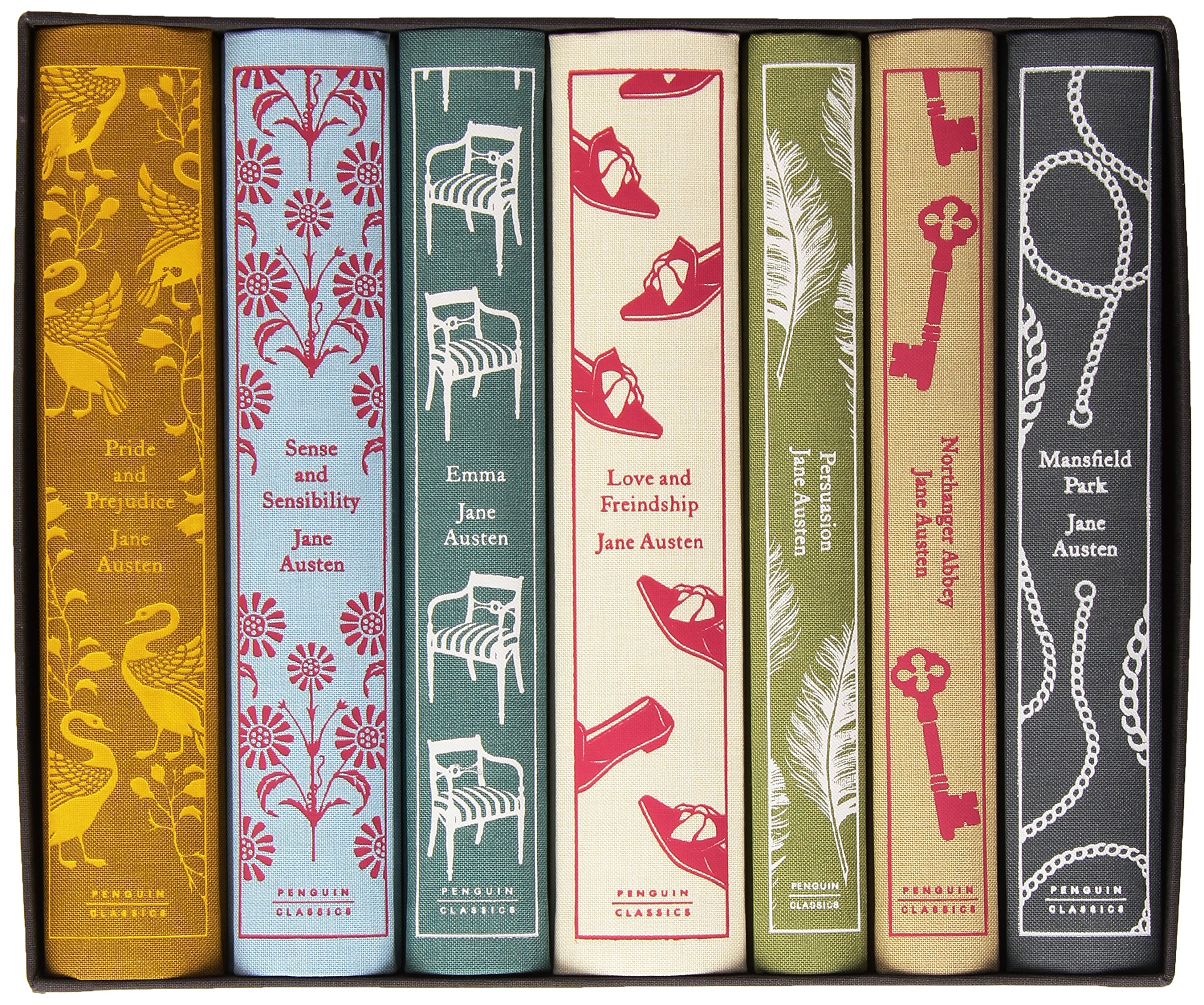

Film may be able to experiment with different points of view (particularly with subjective camera angles), but the objective presence of the camera cannot render ambiguous narration (such as the free and indirect discourse perfected by Jane Austen).

Poetry in Motion

When we think of filmic adaptation, we rarely think of poetry, even though the oft-filmed plays of Shakespeare are in verse and both Griffith and Edison Studio adapted Tennyson’s poetry (Enoch Arden and The Charge of the Light Brigade, respectively).

While filmmakers rarely “adapt” poems to the screen, screenwriters, directors and poets frequently share common goals that cause them to experiment in analogous ways. For example, both Sergei Eisenstein and Ezra Pound were concerned with the nature of language and their own ability to render new art forms appropriate for the times. Both artists also fixated on the Chinese ideogram as their symbol of an entity that could unite both word and image in a seamless new creation. One could argue that Eisenstein’s use of montage in famous films (such as Potemkin and October) does more to meet Imagist (and even Vorticist) ends than Pound’s own poetry or Eliot’s creative use of collage does.

Dada and Surrealist artists, like Salvador Dali, worked to exploit the connections between poetry and film, but perhaps the most famous poet-filmmaker is Jean Cocteau, whose Blood of a Poet, Beauty and the Beast, and Orpheus openly work to exploit the symbolic connections inherent in film’s visual vocabulary.

Perhaps because poetry and film were never seen as commercial or artistic rivals, critics rarely distinguish what one can do that the other cannot. More often than not, critics discuss the poetic elements of film as a way to link the relatively young form with the oldest and most respected of the literary arts.

Works Cited

Bazin, André. What is Cinema? Volume I. Trans. Hugh Gray. U of California P, 2005.

Bluestone, George. Novels into Film. 1957. Johns Hopkins, 2003.

Chatman, Seymour. “What Novels Can Do That Films Can’t (and Vice Versa),” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 7, No. 1, Autumn 1980, pp. 121-140.

Corrigan, Timothy. Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader. Prentice Hall, 1999.

Eisenstein, Sergei. “Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today.” Film Form. 1949. Trans. Jay Leyda. Harcourt, 1977, pp. 195-255.