In the final weeks of the semester, we will individually adapt one chapter, scene, or passage of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale for another medium.

The choice of the chapter, scene, or passage is up to you, as is the medium to which your chosen narrative element will be “translated.” What will *not* be up you is the focus on theme and purpose. Every exercise must:

- articulate an identifiable (and important) theme of the novel

- demonstrate how the chosen chapter, scene, or passage exemplifies this theme

- indicate the ways in which the adaptive medium itself will underscore, enhance, or reinforce the identified theme.

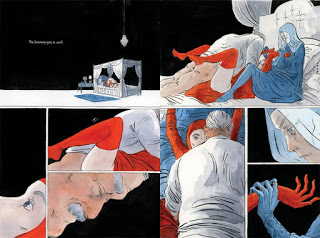

Final drafts, which will be formatted as standard works of expository prose, should be 1100+ words in length. (Note: any multimedia/illustration–which is not required, but may be included–should be appended as supplementary material.)

To be eligible for the 100 points possible, finished exercises must be uploaded to the BlackBoard site (in a Word doc or pdf format) on the designated date at the appropriate time. (Like the “Function of Criticism” paper, the Adaptation Exercise does not have an accompanying rubric. For an explanation why, see the “About Rubrics” page.)

Does the “other” medium have to be new?

No. Atwood’s novel has already been famously adapted into a graphic novel, movie, ballet, and television series. It has also been subtly re-created (or re-treated) in Atwood’s own 2019 “sequel,” The Testaments. If you’re a devotee of “new media,” you may explore the narrative possibilities offered by computer games, social platforms like TikTok, or iterations of virtual reality, but these “new” forms are no more (or less) apt for adaptation purposes than “traditional” movies, magazines, or even performance art.

Choose the medium that best fits your thematic focus.

Why limit the amount of material to be adapted?

There’s a great deal to do/consider in an adaptive treatment of a novel as a whole. Anyone treating the entire text would have to outline *the* core message of the entire narrative before justifying the novelty of his/her totalizing expression. (Consider this: Atwood’s novel already exists, as do a host of media representations of it–so you’d have to sell your audience on why a new iteration is necessary/needed.)

When we focus on a very particular element of the novel (a select chapter, scene, or passage), we can bypass the global concerns of a much larger project while still privileging a specific site of literary interpretation.

How does this relate to the course’s thematic focus?

An exercise that forces students to articulate literary interpretation in “new” ways (that make sense to divergent audiences) is, in and of itself, the creative application of reading skills. We’ve been creatively applying our reading (and writing) skills throughout the semester; this is our final incarnation of imagination.

And didn’t we begin the class with a discussion of ritual dismemberment for divine rebirth while we drafted an argument in favor of the “function of criticism at the present time”? Well, what are we doing now if not “breaking down” Atwood’s text–via careful critical considerations–in order to create a “new product” for our contemporary era?

Theoretical notes, in the end is our beginning:

And why do humans keep on returning to our beginnings, telling a “never ending story” (as we have done in this course)? Because even “divine” rebirths are, in Nietzsche’s parlance, beyond good and evil, and narrative allows us to engage with the endemic “will to power.” Put somewhat oversimplistically, we remember seemingly silly spoofs like the one above far longer than, say, shifting interest rates, because the stories we create for ourselves have more actual value in our lives than many of the arbitrary metrics our society has proffered as indices of progress. (Consider this: the S&P of our course–Shakespeare and Plato–provide more meaningful investment for our collective future than a speculative market that privileges extraction over production. To repurpose Anna Letitia Barbauld’s magisterial “Washing Day“: “Earth, air and sky, and ocean, hath its bubbles,/And [finance] is one of them.”)

Theoretical notes, how and why we adapt:

This Adaptation Exercise presupposes fidelity to the source material is both possible and desirable. This supposition is not shared by all scholars interested in adaptation. Many influential theorists have noted how difficult it is to truly secure a “source” that an adapter could be faithful to in the first place (the parody above, for example, is more indebted to the television series than it is the novel itself), and they have questioned the merit of merely cataloguing instances of transfer. Filmic practices, after all, have shaped modern and contemporary literary forms, as well as publishing trends, so we can no longer even suggest that film or TV treatment is some sort of aesthetic epigone. . . (See The Chicago School of Media Theory for a nice overview of the expansive reach of contemporary theories of adaptation.)