The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms (2nd edition) defines the novel as “a lengthy fictional prose narrative.”

This is an accurate statement, but

- How long is lengthy?

- Does fictional refer to that which is not real or that which is not true?

The six pages of explanation that follow raise more questions than they answer because the term is notoriously nebulous.

As George Eliot famously asserted in “Silly Lady Novelists” (1856), “there is no species of art which is so free from rigid requirements. Like crystalline masses, [the novel] may take any form, and yet be beautiful; we have only to pour in the right elements-genuine observation, humour, and passion.”

Our particular exploration will highlight the historical dimensions that shaped this seemingly form-less modern literary designation.

The Rise of the Novel

Fictional prose narratives are as old as recorded history. Ancient Greek works in long narrative formats, such as Chariton’s Callirhoe and Xenophon of Ephesus’ Ephesian Tale, influenced Roman writers, who penned their own famed tales: Petronius’ Satyricon and Apuleius’ The Golden Ass.

Neither the ancient Greeks nor the Romans, though, categorized these long narrative works as a distinct literary form.

The Heian lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu did not classify her prose narrative, Tale of the Genji (~1010-1021), a novel either, but many critics consider her richly realized tale the first novel because of its finely detailed psychological characterization of “real life” figures. (Virginia Woolf’s 1925 review of Arthur Waley’s translation clearly situates the tale in the novel tradition.)

Contemporary (or medieval) Europe had no literary equivalent to Murasaki’s monumental narrative achievement. Medieval Europe’s recorded literature, in fact, is dominated by fables, legends, and chivalric tales. These fantastic works, which exist in verse as well as prose forms, are broadly classified as “romances.”

The “modern” novel (or the novel form as we know it) emerges in the 18th century. Popular works of fictive prose from the era, such as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) or Charlotte Lennox’s The Female Quixote (1752), articulate the “probable” adventures of recognizable, contemporary characters. Many of these tales involve quotidian accounts of bourgeois life.

This bourgeois focus reflects the readership of the form, as well as a new cultural emphasis on the middle classes. As Nancy Armstrong argues in Desire and Domestic Fiction, the novel displaced “the intricate status system that had long dominated British thinking” with representations of “an individual’s value in terms of his, but more often in terms of her, essential qualities of mind.”

Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel underscores the philosophical and social shifts that facilitated an individualist focus on the bourgeoisie while also privileging the narrative movement toward realism. According to Watt, the genius of a writer like Jane Austen resides in her ability to unite the psychological depth of Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novels with the humor and pacing of Henry Fielding’s picaresques.

Realizing a Reading Public

Subsequent critics have contested many of Watt’s claims and added much needed nuance to his literary history. His “novel” argument remains influential, though, because Watt’s work is the first to articulate the new methods of engagement writers had with readers in the burgeoning print market.

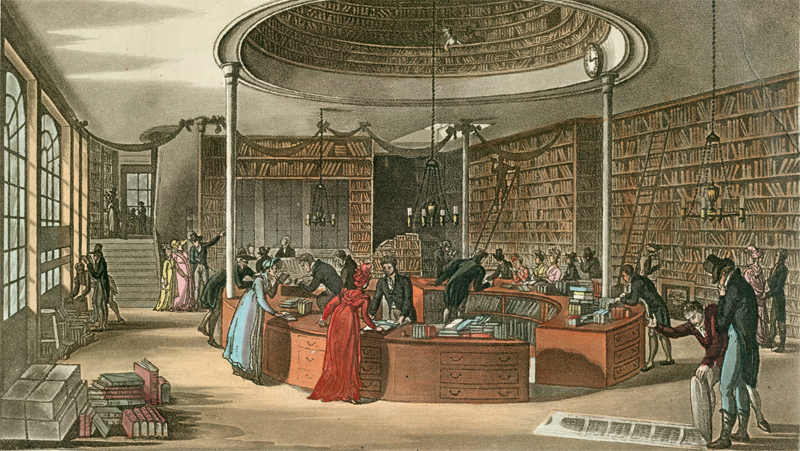

The English language novel emerged when literacy rates in England vastly increased. As educational attainment spread and workers’ wages improved (creating more disposable income), printing and book selling became highly profitable. New works explicitly crafted for this expanding market were sold alongside educational and devotional texts. These new works provided finely-detailed accounts of “ordinary” people (who may be entangled in extraordinary circumstances) displaying modern sensibilities and interests.

While these new methods of narrative address often eschewed oral modes and fabular elements, they were not unidirectional movements toward what we might now term realism. Not only did “factual fictions” like Fantomina; or Love in a Maze (1724) include obvious fabrications and implausibilities, but fantastical elements continued to suffuse popular “romances” such as The Castle of Otranto (1764). (For more on the “marvelous” nature of these fictions, see Sarah Tindal Kareem’s Eighteenth-Century Fiction & the Reinvention of Wonder.)

What separates a Renaissance narrative series like Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532-1564) from the Neoclassical satire Gulliver’s Travels (1726) isn’t the presence or absence of giants; it is Swift’s conscious address of a middle-class readership.

The Power of Print Periodicals

Novels were not the only written commodities bought and sold in emerging print markets. Robert Walker fueled a mini Renaissance in Shakespeare’s popularity (and performance) when he marketed cheap copies of the Bard’s plays. This dramatic expansion, though, never reached the impressive circulation rates of popular periodicals. Richard Steele and Joseph Addison’s The Tatler, The Spectator, and The Guardian were not just read by their numerous subscribers; they were also avidly devoured by coffee house patrons, who would pay admission to local businesses for the privilege of reading the latest editions.

Early novels were also consumed in a periodical format. Eighteenth-century publishers divided long narrative fictions into separate print volumes for lending libraries–a printing practice that led to the dominance of the “triple decker novel” in the Victorian era. The phenomenal success of Charles Dickens’ The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (published in 1836 through 1837) showcased the profitability of serialization. Many Victorians would read novels in sequential installments.

Periodicals profoundly shaped the production of short fiction as well. According to William Boyd, the new magazine and periodical market actually “revealed to writers their capacity to write short fiction.” Finite tales of limited length had always been part of oral and folk traditions; now there was a “publishing forum for a piece of short fiction in the five to 50-page range.” Boyd’s “A short history of the short story” may not broach the vexed issue of length in fiction (an issue that has long troubled distinctions between novellas and novels), but it does highlight the dynamic relationship between publication venue and fictive form.

Literary Markets and the Commerce of Fiction

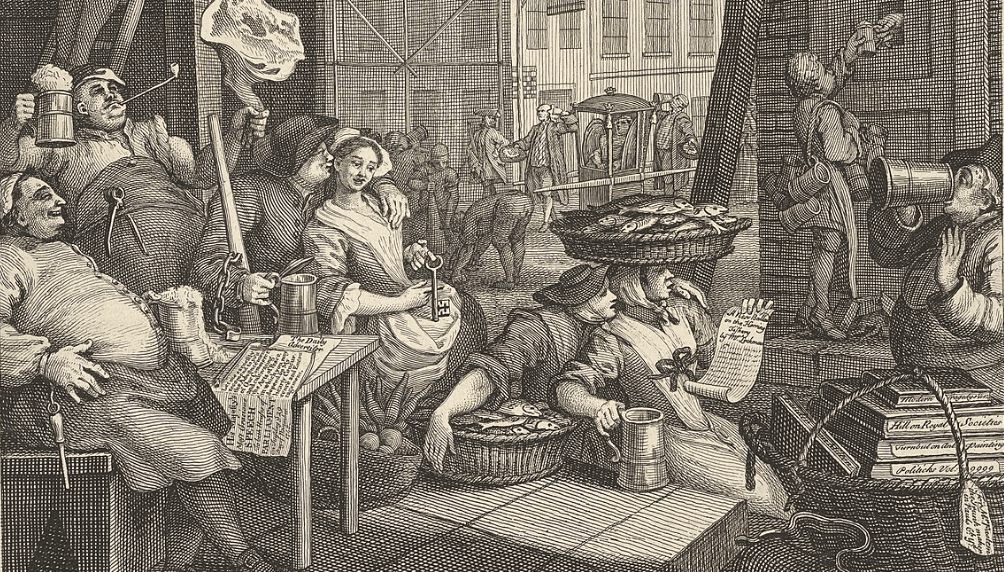

Novelists were well aware of the literary marketplace. Samuel Richardson worked for decades as a printer before he published his first novel, and Henry Fielding turned to novel writing as a way to earn an income when the Licensing Act of 1737 ended his career as a dramatist. Dickens prodigious output was designed to maximize profit, as were his American book tours, which sought to recoup some of the lost income from lax copyright laws (and American piracy of his publications).

The undeniable link between commerce and composition caused early critics, and even some novelists, to question the literary value of the novel. Interestingly enough, the man widely cited as the “Father of Capitalism,” Adam Smith, made a case for the refinement and delicacy of the “romances” of Richardson (and Voltaire) in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).

When critics now question the quality of particular novels, they, like George Eliot before them, indict “silly” or inconsequential practitioners. They do not denigrate the commercial form itself.

Novel Reading: Shameful or Virtue Rewarded?

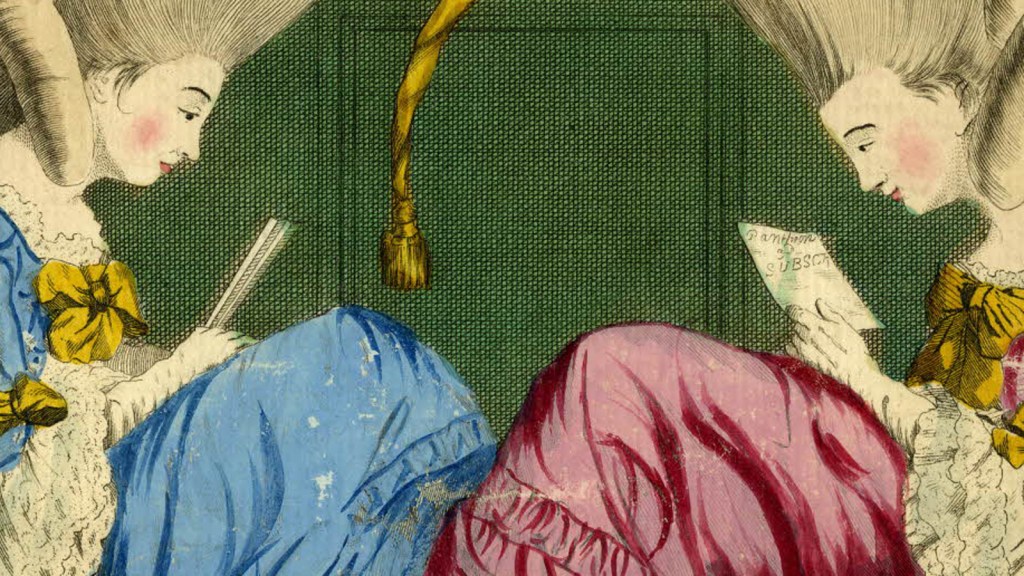

Admittedly, Smith’s defense of novel forms (which were still termed “romances” at the time) is not primarily aesthetic. It is moral. Eighteenth-century critics did not worry that the novel would denigrate literature (many refused to entertain the notion that the popular form could be literary in the first place). They worried about the effects this (low) form would have on susceptible young readers, who were more often than not female.

Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey humorously highlights some of these fears: Catherine Moreland runs the risk of losing her new friends when she cannot successfully distinguish real life from the fantastic fictions she has been reading. What Austen presents as a catalyst for the growth and development of a young female protagonist, contemporaneous critics would condemn as a modern danger young women should avoid.

Much of the early animus against the novel replicated age-old arguments against mimesis. Representations of life, even ones purporting to be faithful, were faulted for not being “real” or “true” (and for encouraging impressionable readers to focus on sordid or scandalous elements). Seeing little of value in the imaginative world represented in the novel, critics urged contemporary readers to select more edifying texts that served an educational function.

This thinking is no longer common. Novels are now considered part of a “Great Tradition” that has changed the possibilities of art (and artistic expression). Interestingly enough, part of this “tradition” has been revaluing what could be considered “moral sentiment” in light of modernist celebrations of formalism (c.f. the obscenity charges brought against Ulysses).

A Woman’s Sentence?

The finely detailed characterizations of Northanger Abbey demonstrates novel reading was never just for women: Henry Tilney is as avid a reader of novels as Catherine Moreland, and even the brutish John Thorpe enjoys daring work like The Monk. That said, the satiric plot of Austen’s comedy of manners confirms women were the primary audience.

As Armstrong contends in Desire and Domestic Fiction, “novels early on assumed the distinctive features of a specialized language for women. A novel might claim a female source for its words, concentrate on a woman’s experience, bear a woman’s name for its title, address an audience of young ladies, and even find itself criticized be female reviewers.”

The first sustained work of criticism that acknowledged this gendered history is Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929). This collection of interrelated essays expounds on ideas Woolf put forward in 1928 lectures on “Women and Fiction” (both given at Cambridge University), famously invoking the elliptical conception of a “woman’s sentence.” In the decades that followed, French feminist critics would explore the possible “sex” of writing itself in concepts such as écriture féminine whereas Anglo-American scholars would focus on the material aspects of literary production and consumption.

Surveying the Modern World of Fiction

Our survey of the British novel will navigate the decidedly modern world of narrative fiction. This navigation won’t resolve the issue of length–not in the least because we’re beginning with a work many consider a novella (Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko)–nor will it secure the nature of “truth” in fiction. It will, though, highlight the modern market conditions that allowed the novel, as we know it, to flourish, all the while underscoring the continued relevance of early generic debates. (This historical lens will help us understand how Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day can both be considered exemplars of contemporary British fiction.)